History of Langston High School

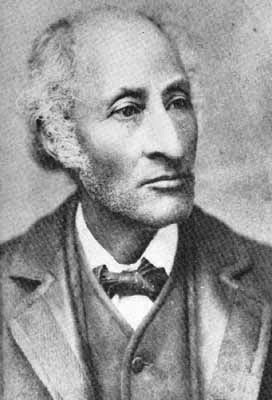

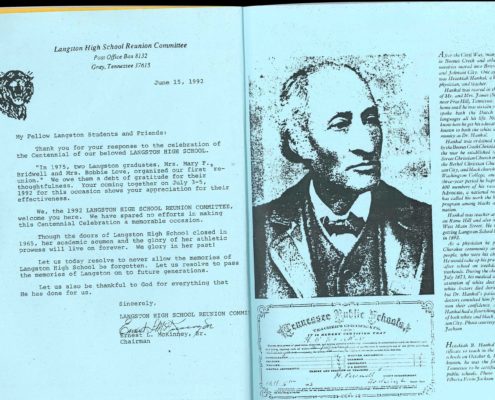

Dr. Hezekiah Hankal, one of the Founding Fathers of Johnson City, purchased town lot number 12 from Henry Johnson in June 1869 for $300 as a site for the Colored Christian Church. Born a slave in 1825, he was reared in the Dutch home of James and Nancy Hankal in what is now Gray, Tennessee and was fluent in Dutch and several foreign languages. Dr. Hankal gained notoriety for his extraordinary medical skills during the cholera epidemic of 1873, establishing an interracial medical practice that continued until his death in 1903. Dr. Hankal was elected alderman in Johnson City in 1887 and helped start a number of historic black churches throughout Northeast Tennessee.

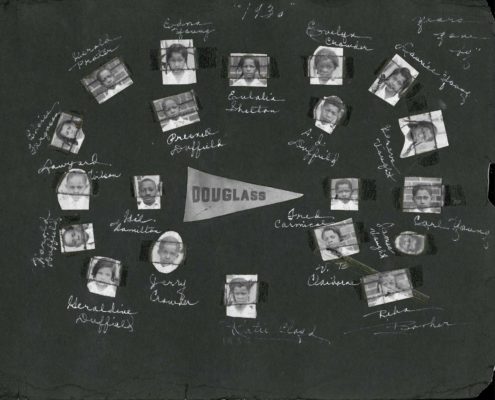

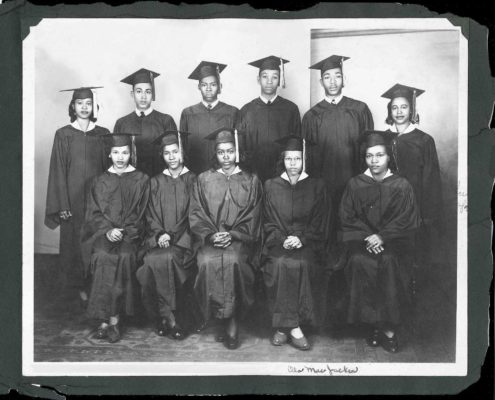

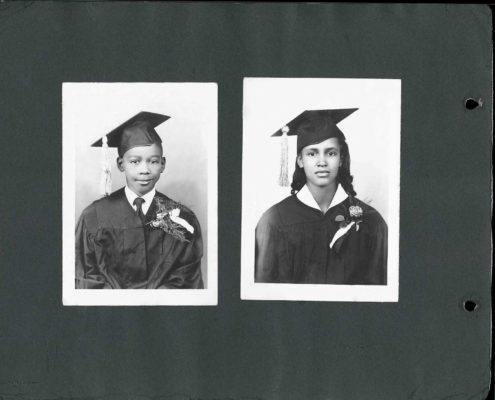

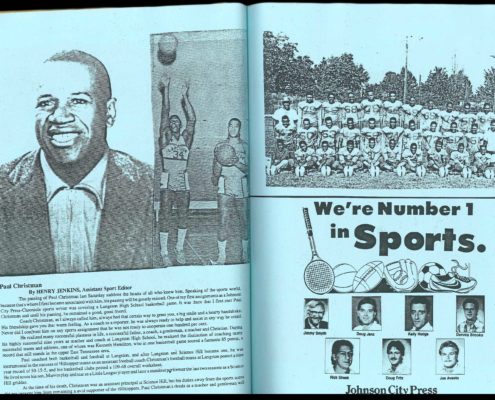

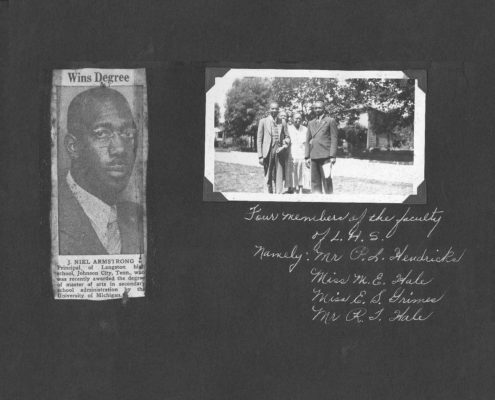

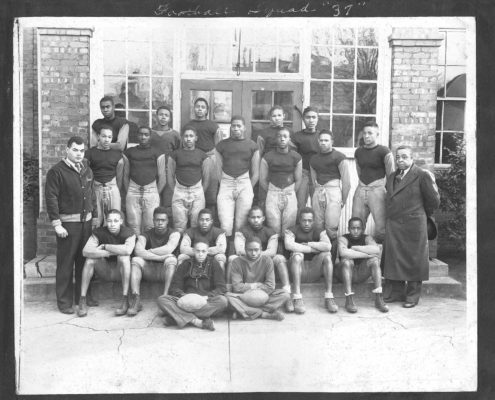

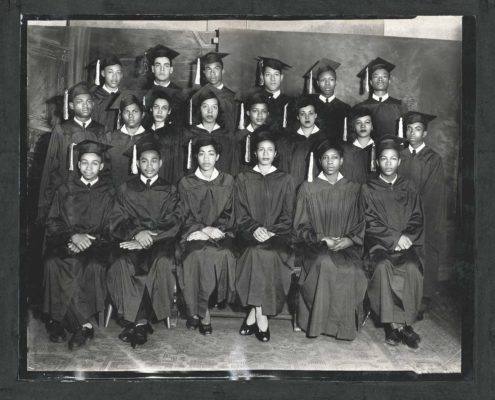

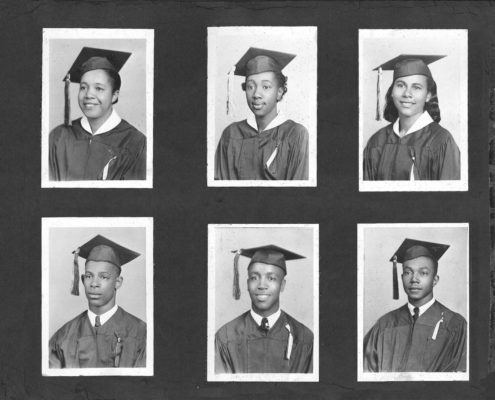

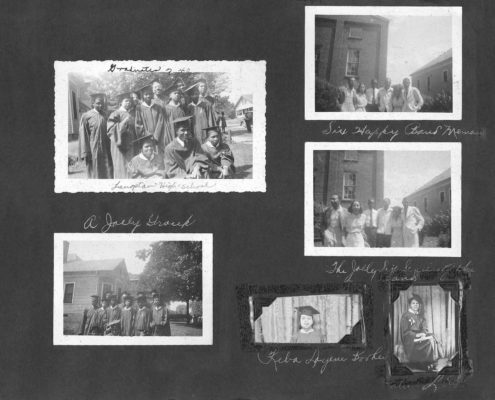

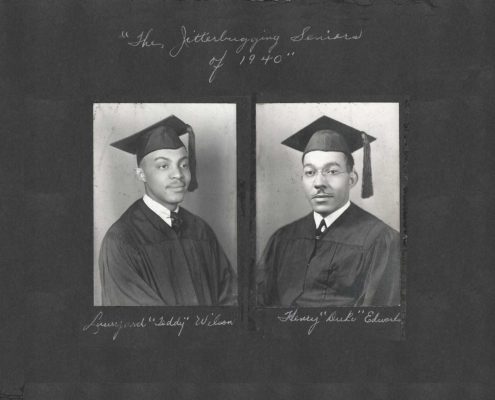

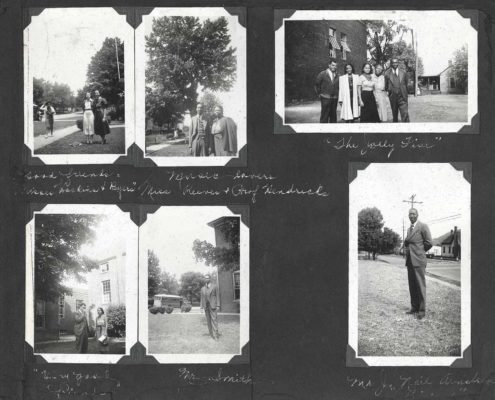

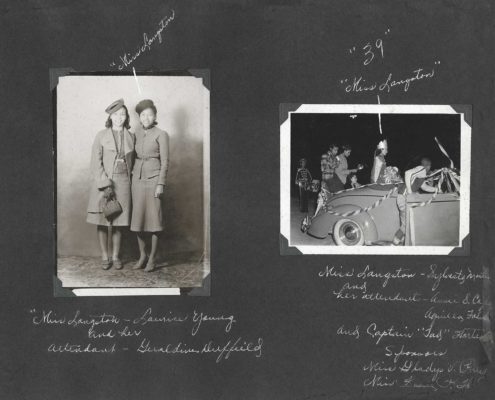

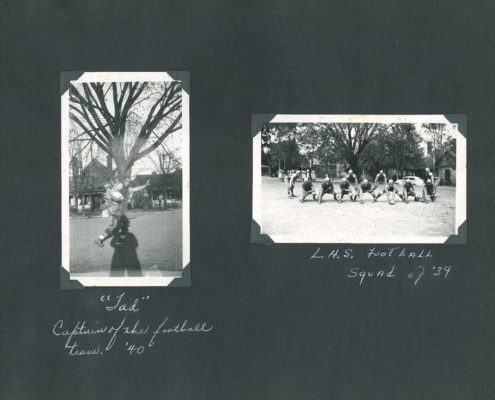

Johnson City began a school building program in 1892 and one of the three newly designated schools was established for colored children. The school was named Langston Normal School for noted black leader John Mercer Langston, a Congressman from Virginia. Dr. Hankal, along with Dan Reeves and Alfred Hyder, were instrumental in securing approval for the new school which was located at the corner of Myrtle Avenue and Elm Street.

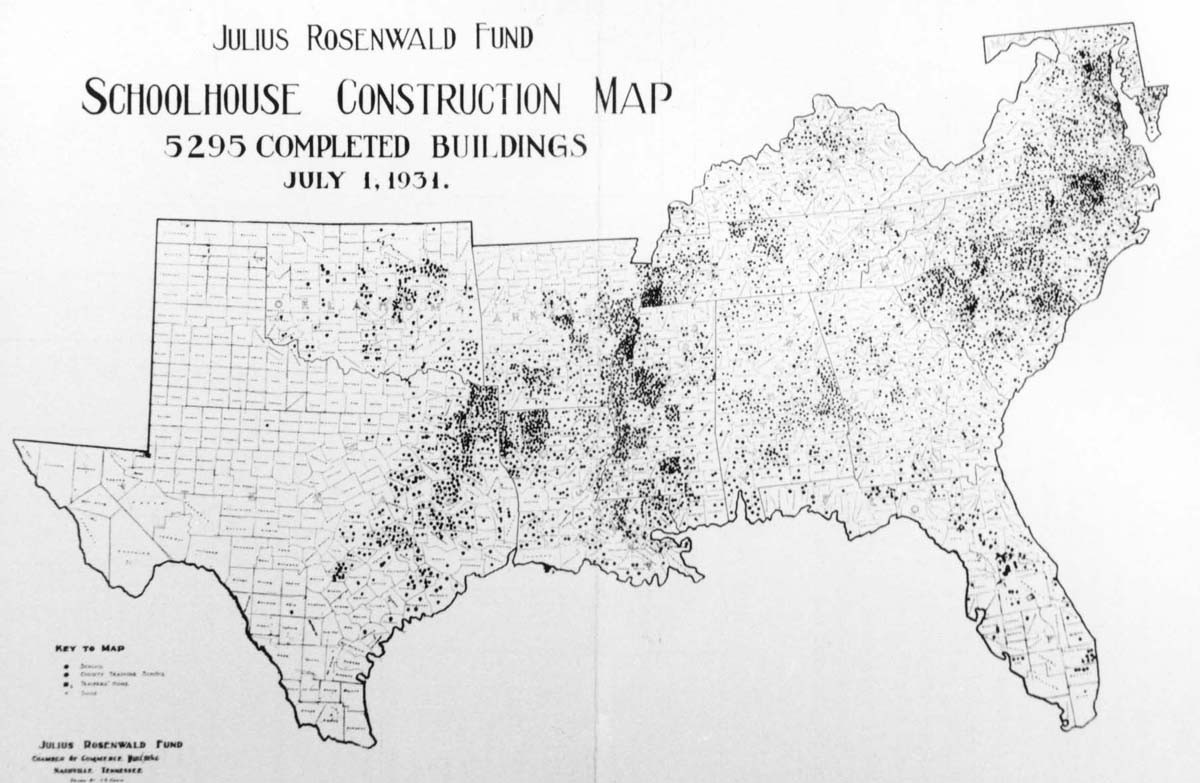

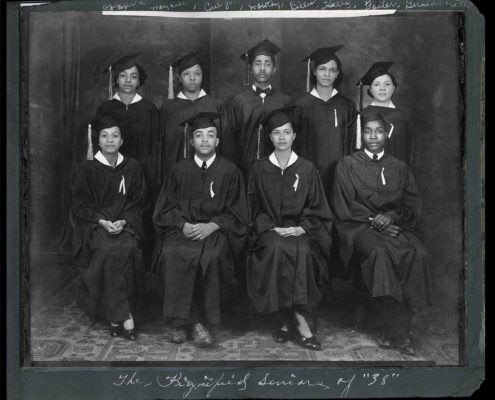

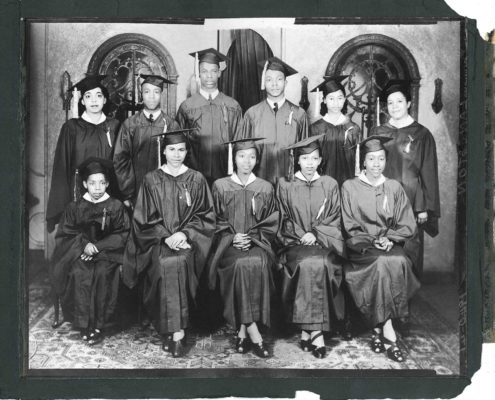

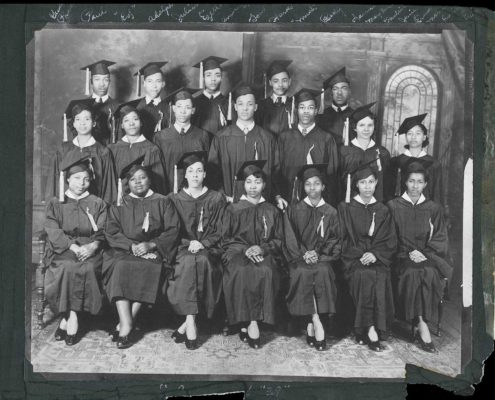

In conjunction with a 1925 renovation of the school, Langston High School is a recipient of Rosenwald funding for the gymnasium. Booker T. Washington of the Tuskegee Institute and Julius Rosenwald, philanthropist and president of Sears Roebuck, built state-of-the art schools for African- American children across the South. The effort has been called the most important initiative to advance black education in the early 20th century.

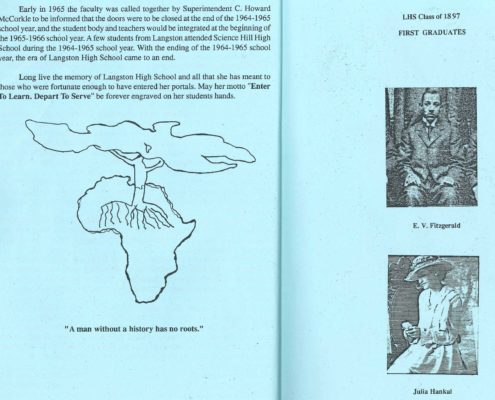

When a 1954 Supreme Court ruling declared segregation in education unconstitutional, Rosenwald Schools became obsolete. Once the pride of their communities, many were abandoned or demolished.

LEAD is the grassroots organization in Johnson City, Tennessee spearheading the effort to save the Langston High School.

Significance of Rosenwald Schools

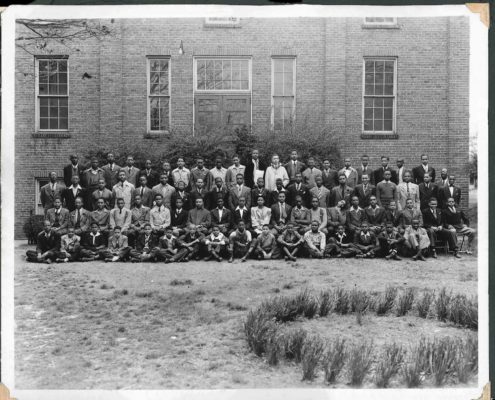

Beginning in 1912, the Rosenwald school building program, under the auspices of Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute (now Tuskegee University), began a major effort to improve the quality of public education for African Americans in the South. By 1928 one in every five rural schools in the South was a Rosenwald school; these schools housed one third of the region’s rural black schoolchildren and teachers. Thousands of Rosenwald Schools have been abandoned and lost over the years, but many have been given new life as thriving community centers, studios, museums, and even private homes.

Attending a Rosenwald School put a student at the vanguard of education for southern African-American children. In 2002, the National Trust joined forces with grassroots activists, local officials, and preservationists across the country to help raise awareness of this important but little-known segment of our nation’s history, placing Rosenwald Schools on its 11 Most Endangered Historic Places list. Of the 3,537 schools, shops, and teacher homes constructed between 1917 and 1932, only 10–12 percent are estimated to survive today.